“Nothing about us, without us.”

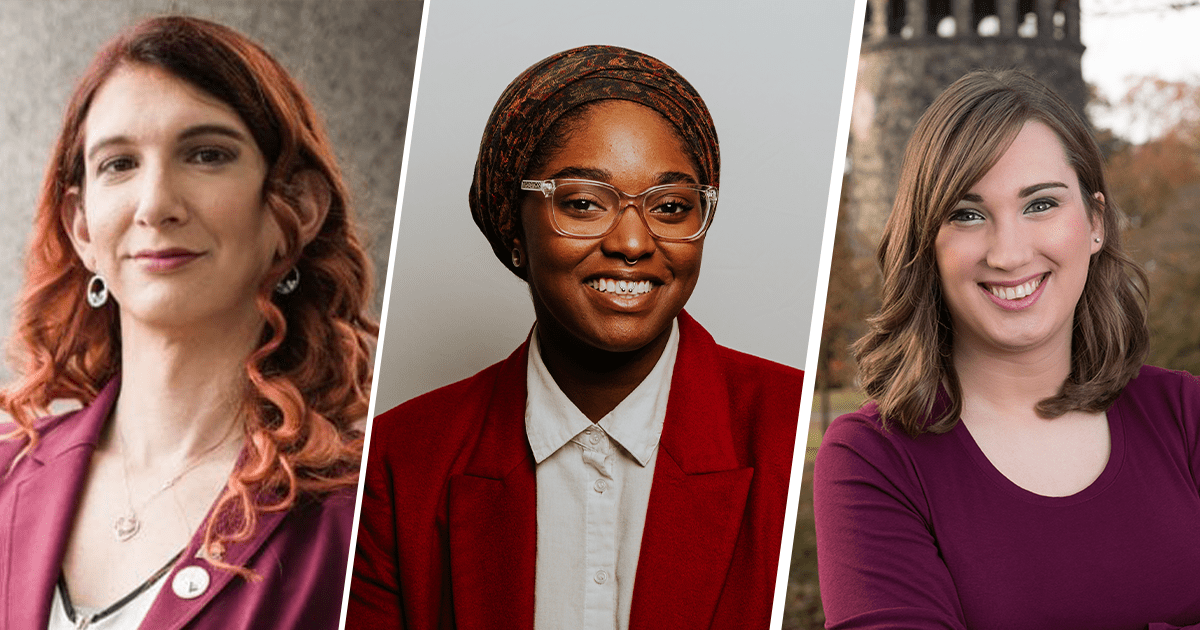

Those words are often used by autistic advocates (and other disabled activists) to demand inclusion and justice. This World Autism Month, we turn to a leader in the movement for disability rights and political representation, Rep. Jessica Benham, for her thoughts on the state of autism awareness and disability rights.

Victory Institute: As the first autistic LGBTQ lawmaker, what does World Autism Month mean to you? How can activists and officials center the voices and experiences of autistic people?

Jess Benham: This month is one that has been historically really difficult for me because it’s a month where parents, caregivers, and support organizations tend to prioritize the feelings of parents and support professionals and not so much the perspectives of autistic people. We see this more widely in discussions about disability policy, where non-disabled voices are prioritized over the voices of disabled voices, I think the month echoes that.

I think it is really important that folks who are wanting to talk about autism during April, that they highlight the voices of autistic people, and not just prominent White autistic people, which happens very often. Most Autistic people are also more likely to be in the LGBTQ+ community than the population at large. People will say, ‘oh well you know most folks who get a diagnosis are White men’ and well that’s a problem. Most autistic people are not White men, but White men are overrepresented in diagnosis due to the barriers of diagnosis for girls and for Black and brown folks. I really encourage folks to take time this month to lift up the voices of autistic people who don’t get heard or highlighted a lot.

VI: Why is it important for neurotypical folks to understand how the intersections of disability, sexuality, and gender impact LGBTQ autistic people?

JB: I think those are conversations we often have within the autistic community. We have known for a long time, particularly about gender, that autistic people are more likely to be trans or nonbinary than the population at large. There’s a lot of reasons why that can be the case but it is something we have known to be true a lot longer before the research popped up. I think that happens a lot, research comes after people who have had that lived experience already knew it to be true. But I think it’s important to identify because it has practical implications.

I currently am co-sponsoring a bill with House Rep. Brian Sims that will provide comprehensive sex education. When he asked me to be a prime cosponsor, I said yes, but only if we made changes to the bill to ensure that it is inclusive of folks with disabilities, especially folks with developmental and intellectual disabilities because they are often left out of sex ed. It matters because folks with developmental and intellectual disabilities are more often abused, assaulted, and/or neglected. Not just to disabled people, but to an integrated classroom that disabled people have sex, and not just straight sex.

When we are thinking about gender, what does reproductive justice looks like? And addressing how the state enables or often disables folks from being able to care for kids with disabilities, or really gets in the way of people with disabilities being able to parent. So, when we are thinking about the intersections of gender, disability, sexuality, race, etc. that is really informative when I am thinking about policy.

VI: What does disability rights and justice mean to you?

JB: I think about disability rights as a framework that has been around for a while, it makes sure that disabled people are included in society and that is an important frame, but it is a frame that often ends up centering White disabled people, and more often than not, White disabled wheelchair-using people. There have been a lot of movements forward for disabled people that have used the disability right frame and I really don’t want to discount it, because it played a major role in getting our civil rights.

But for me disability justice is broader, it is a frame that centers the experiences of women and femmes, and specifically Black and Brown women and femmes. That, to me, is really important because when we create policy and approach policy with a lens that centers the most marginalized communities, that helps everyone. It is a framework that was created by a group of Black and Brown disabled women and femmes, it’s about understanding disability justice as central to justice more broadly. Just about every issue of injustice in our world can be tied back to disability at some point.

For example, when we think about environmental justice, a movement that centers Black and Brown communities that have been hit hardest by pollution, the concentration of pollution in those communities literally disables people (pollution can cause cancer, asthma, etc.). Disability justice is about understanding the ways in which disability is foundational whenever we are thinking about justice. I tend to operate more from the disability justice framework because I see every issue as something that very much is about disability but particularly, I understand the issues of injustice we face in our world as the intersection of ableism and anti-Blackness, and that for me is what disability justice is about.

VI: What needs to change in order to get more folks with autism and other disabilities elected to public office?

JB: I think there are two factors at play. The first being, that there are more disabled people in elected office that we know about because of the role that stigma plays in folks choosing not to disclose or folks not even being aware that their lived experiences count as a disability. The second part of that is the structural barriers that really prevent disabled folks from running.

For example, in Pittsburg, a lot of places are hilly, if you are someone who has a mobility disability, door knocking is really tough but if your opponents are able to door knock it’s a really effective way of reaching voters. It’s much harder to get voters on the phone or via text message, so thinking about how we can make campaigning more accessible. I know some candidates will door knock with an able-bodied person and have them walk up to say, hey there is a candidate down your steps that would like to talk to you.

Another problem is that disabled people do not tend to have networks of big donors and in the world that we live in, running for office requires a significant amount of fundraising. In the state of Pennsylvania, there are no campaign limits but that can be a disadvantage for folks who do not have a wealthy network. It’s tough, it is something that is definitely doable, it is just harder for folks like me.

VI: In 2019 you participated in Victory Institute’s Candidate and Campaign Training. How did the training prepare you to run for office?

JB: The training was incredibly thorough which I really appreciated. I had been around campaigns before but I had never worked on one, so to really get a deep understanding of how campaigns work from press relations to field to marketing, etc., was really cool! My team won the campaign presentation at the end, so I felt very good about that. I technically feel like my election was the second campaign I won. The training prepared me for what each piece of campaigning would look like and that was really helpful. I then created a campaign plan for my campaign that I took to stakeholders to help them understand why it was important to invest early. There were several unions and stakeholders that were willing to invest early in my race, in part because I showed that I was prepared to use that investment wisely, that I had a plan. I knew how to make that plan because of Victory’s Candidate and Campaign training.

This interview was edited for clarity.